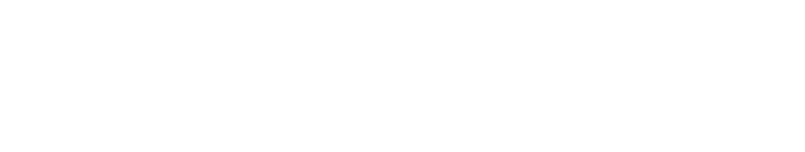

In late 2015, the family of Erica Wilson (1928-2011) donated many of her needlework creations to Winterthur. Quite modern compared to the majority of Winterthur’s decorative arts collection (most of which were made before 1860), Wilson’s works are an exciting new addition to the collection because they exemplify the continued importance and history of needlecraft in America into the twentieth century.

Known as “America’s First Lady of Stitchery” and the “Julia Child of Needlework,” Wilson was a key leader of the needlework revival that began in the 1960s. One of the most prominent and successful needlework entrepreneurs of the second half of the twentieth century, Wilson inspired a new generation to try their hand at traditional crafts that were long out of fashion.

Wilson was born in Tidworth, England, in 1928 and was raised in England, Scotland, and Bermuda. According to family tradition, it was Wilson’s mother who suggested she consider attending the Royal School of Needlework in London (RSN), a fateful decision that ultimately shaped Wilson’s life and career.

Founded in 1872, the RSN revived the art of hand embroidery that had almost disappeared with the rise of machines for textile production. The school quickly attracted students and staff. By the beginning of the 20th century, RSN employed about 150 women, who taught classes and worked special commissioned projects, such as the gold embroidery on Queen Elizabeth II’s Purple Coronation Robe of Estate. The project was worked during Erica Wilson’s time at the school (1948-1954), and it took a total of 3,500 hours to complete.

Royal School of Needlework employees embroidering Queen Elizabeth II’s Coronation Robe of State in 1953. From http://www.thehousedirectory.com/blog/royal_school_of_needlework

Queen Elizabeth II with her coronation maids of honor, 1953. From http://orderofsplendor.blogspot.com/2012/02/flashback-friday-queens-coronation-gown.html

Several items now in the Winterthur collection highlight Wilson’s training in traditional needlework techniques, such as crewelwork, whitework, blackwork, and goldwork.

Crewelwork “Elizabethan Lady,” by Erica Wilson (1928-2011), before 1973. Gift of the Family of Erica Wilson 2015.47.5.2.

Whitework “Elizabethan Lady,” created by Erica Wilson at the Royal School of Needlework, London, circa 1948-1952. Gift of the Family of Erica Wilson 2015.47.5.1.

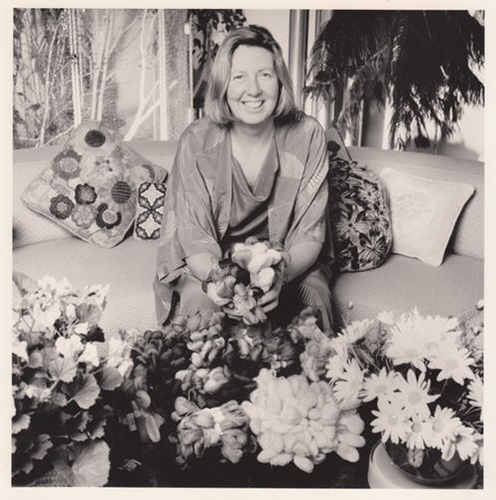

Blackwork vest panel embroidery, by Erica Wilson, after 1954. Gift of the Family of Erica Wilson 2015.47.7.

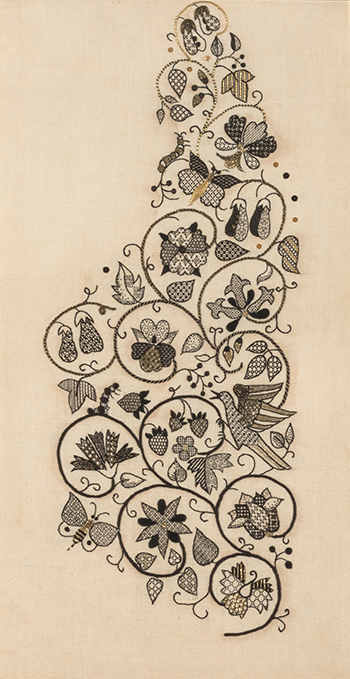

Goldwork embroidery, by Erica Wilson, after 1954, Gift of the Family of Erica Wilson 2015.47.6.

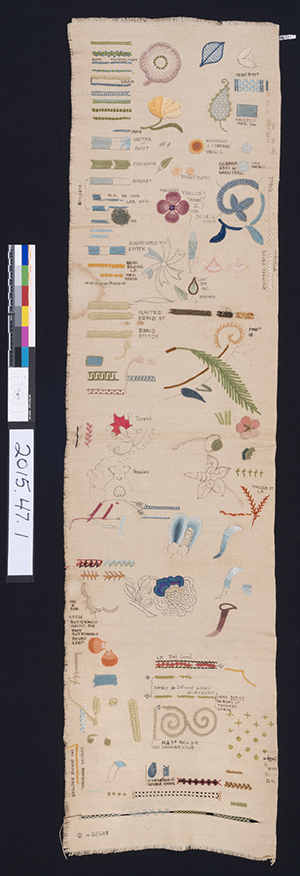

As a student, she proved her proficiency in these different techniques by creating samplers. Her long, narrow reference sampler shows her mastery of the seven basic stitches of needlework (stem, satin, chain, cross, back, weaving, and filing) and also her ability to work in a variety of materials, including silk, wool, and metallic thread.

Reference Sampler, created by Erica Wilson at the Royal School of Needlework, London, circa 1948-1952. Gift of the Family of Erica Wilson 2015.0047.001.

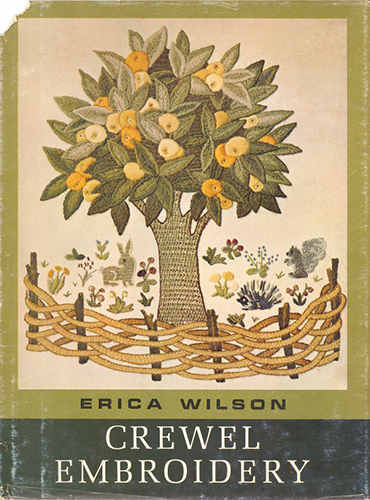

After graduating in 1952 with a Diploma in Embroidery and Design, Wilson stayed on at the Royal School an additional two years as an “Instructress.” In 1954, she was recruited by Margaret Parshall, an American visiting the RSN, to teach at a needlework school she was establishing in Millbrook, New York. Wilson’s reputation in the United States blossomed quickly and led to new opportunities: additional teaching invitations (including at the Cooper Hewitt School in New York City), the production of popular correspondence courses that taught the technique of crewelwork (or embroidery with wool thread), and in 1962, the publication of her first instructional book, Crewel Embroidery. Published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, the book was a hit, selling over a million copies. Its success subsequently led to the publication of over a dozen more books over the next several decades.

Erica Wilson’s first publication, Crewel Embroidery, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1962. http://bangordailynews.com/2012/04/23/living/by-hand/the-embroidery-influence-of-erica-wilson-lingers-on/

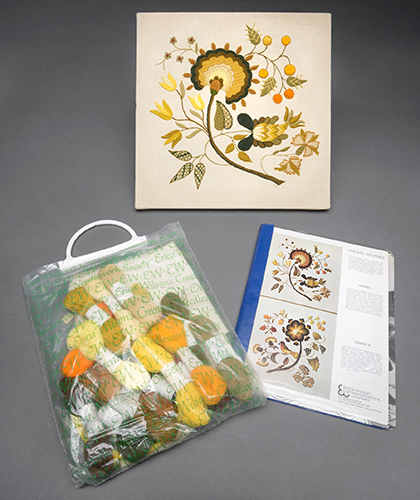

Encouraged and supported throughout her career by her husband and business partner, famed modern furniture designer Vladimir Kagan, Wilson also pioneered several new methods for introducing novice audiences to needlecraft. When creating her custom designs, Wilson branched out beyond historic tradition. She designed whimsical patterns that appealed to modern crafters and drew inspiration from some of her favorite children’s books, including the stories of Beatrix Potter. Many of these designs were shared through “Erica Wilson’s Creative Needlework Society,” established in 1971 as a division of the Book-of-the-Month Club, Inc., that sent out needlework projects to tens of thousands of society members.

Hunca Munca from Beatrix Potter’s A Tale of Two Bad Mice (1904), by Erica Wilson (1928-2011), around 1972. Gift of the family of Erica Wilson 2015.47.21.

Peter Rabbit, “Love is a shared umbrella,” by Erica Wilson (1928-2011), before 1979. Gift of the family of Erica Wilson 2015.47.20

Jacobean-scalloped flower crewel correspondence course kit, instruction manual, and completed embroidery, distributed by Erica Wilson’s Creative Needlework Society, after 1971. Gift of the family of Erica Wilson 2015.47.70.1 and 2015.47.68.1

Her most visible public endeavor was her television program Erica, which Wilson hosted beginning in 1971 on Boston’s PBS affiliate WGBH and broadcast nationally. Episodes of the program focused on an individual technique such as cross-stitch and bargello or themes like sentiments in stitches.

Bargello spot sampler, by Erica Wilson (1928-2011), before 1973. Gift of the family of Erica Wilson 2015.47.2.

During the 15-minute show, Wilson gave a brief history of the subject, displayed several historic examples, and used her own works in progress to break down and teach her viewers basic techniques. Erica was filmed in the studio next door to where Julia Child’s The French Chef was filmed, and Wilson’s efforts to “demystify” the art of embroidery earned her the nickname “The Julia Child of Needlework.” (OpenVault by WGHS has recently digitized nearly 24 episodes of Erica, which can be viewed online).

Wilson’s legacy lives on through the over 80 examples of her work now in the Winterthur collection. Her works will aid future scholars studying American textile and business history, and as she always aimed to do, will continue to inspire new people to embrace the beauty and fun of embroidery.

Several of Erica Wilson’s needlework pieces will be on display in May 2017 in Collecting for the Future: Recent Additions to the Winterthur Collection.

Post by Nalleli Guillen, Sewell C. Biggs Curatorial Fellow, Museum Collections Department, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library

References

Fox, Margalit. “Erica Wilson Dies at 83; Led a Rebirth of Needleworking,” The New York Times, December 13, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/14/nyregion/erica-wilson-dies-at-83-led-a-rebirth-of-needleworking.html

Hilker, Anne. Unpublished interviews with Vladimir Kagan on his late wife, Erica Wilson, May 9 and 10, 2014. (Special thanks to Anne, who presented her knowledge of Erica Wilson’s life and work during a work shop at Winterthur’s 2016 Needlework Conference and graciously shared selections of her Ph.D. dissertation research with us).

Reif, Rita. “Her Home is Also Her Studio—And She’s Very Happy About It,” The New York Times, December 20, 1971.

Sikarskie, Amanda Grace. “Erica Wilson: The Julia Child of Needlework.” http://openvault.wgbh.org/exhibits/needlework/article#footnote-2

Wilson, Erica. Crewel Embroidery. New York: Charles Scribern’s Sons. 1963.

Wilson, Erica. Erica Wilson’s Embroidery Book. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1973.