Pair of oversize mugs owned by Isaac Gustav Clason (1748-1804). Made in China, ca. 1792. Porcelain (hard paste). Gift of Julie and the late Carl M. Lindberg 2014.29.1.1, .2.

An extraordinary pair of Chinese export porcelain mugs recently donated to Winterthur and featured in our exhibition, Collecting for the Future: Recent Additions to the Winterthur Collection, has a fascinating private as well as global history.

Likely produced in the late 1700s in Guangzhou (Canton), China, as a special custom order, the mugs were exported to Gothenburg, Sweden, by the Swedish East India Company (S.E.I.C.). According to the Swedish language publication Med Hammare Och Fackla (1940), these items descended through generations of the Clason family and became a crucial part of their holiday celebrations. Every Christmas, the mugs were filled with local beer and shared communally to toast the family’s future prosperity. In their native Swedish they exclaimed “Oss väl och ingen illa!,” or, roughly translated, “For us well and no one bad!” The two mugs are colossal (about 8 inches tall and six inches in diameter) and accommodate over a gallon of liquid each! This likely made for a festive Christmas celebration at the Clason home and is just one of the many stories embedded in these unique items.

Compare our Swedish market mug with a typical coffee mug. While our modern mugs hold about 150 mL, the Swedish mugs hold over 4,700 mL!

Beyond this convivial family history, these vessels also shine a light on the highly productive trade relationship between China and competing European powers in the 18th century. While other European countries began trading with China as early as the 1500s, Sweden did not begin trading directly with them until well into the 18th century (60 years after the Portuguese and 30 years after the Dutch and British).

This punch or hong bowl (a very popular souvenir among traders) shows the blue and yellow Swedish flag (far left) alongside the British and Dutch flags. Made in China, ca. 1780-90. Porcelain (hard paste). Gift of Leo A. and Doris C. Hodroff 2000.61.73

In 1731, the Swedish government granted the first of four charters to the new Swedish East India Company, establishing their monopoly on the nation’s trade with China. During their 82 years in operation, the S.E.I.C. sailed 132 voyages to China on 35 ships. The one-and-a-half-year roundtrip could be treacherous. In fact, the S.E.I.C. lost eight ships during their years in operation. This included the great East Indiaman Götheborg, which tragically sank just outside its home harbor after striking rocks on its return from China in 1745. An extensive marine archaeological excavation of the wreck (conducted from 1984–92) produced an extensive documentary record of the mid-18th-century Swedish-China trade and led to the full scale reproduction of the ship in 2005!

The rebuilt replica of the East Indiaman Götheborg left on her first voyage from Gothenburg to China in October 2005. Image from http://www.gotheborg.com/project/project_introduction.shtml

The Swedish market desired traditional Asian export wares and designs already popular with other Europeans. However, Swedish consumers also commissioned unique items like Winterthur’s pair of mugs, which speak much more specifically to Sweden’s aspirations on the world stage in the 18th century and the impact the melding of global influences had on the material record at that time.

From the start, the S.E.I.C. purchased underglaze blue and white wares and also items with additional overglaze enameling, runaway favorites among European consumers that they could sell for big profits. In addition, Swedes who could afford to, commissioned custom wares decorated with their family crests. Scholars estimate that as many as 300 Swedish noble families sent orders for custom armorial designs to China via the S.E.I.C. to be reproduced on their dinner services.

Blue and white pudding plate. Made in China, ca. 1743. Porcelain (hard paste). From the 1905 excavation of the wrecked ship Gothenburg by James Keiller. In the Collection of AntiWest company of Gothenburg. Image from http://www.gotheborg.com/~gothebor/exhibition/exhibit_1-29.shtml

Plate from the estate of Gullbringa, which was owned by Hans Henrik Clason, a captain in the Swedish East India Company on four different ships between 1782 and 1794. Image from http://www.gotheborg.com/exhibition/exhibit_64-147_armorial.shtml

Winterthur’s oversized mugs fall into a special subset of Swedish commissions for customers who wanted to honor their Swedish heritage and affluence with more than the standard armorial design. These items, in many cases in spectacular forms, are decorated with highly detailed topographical landscapes of real Swedish locations and feature detailed settlements, manors, castles, and fortifications.

For example, four surviving covered punchbowls with matching underdishes decorated with topographical designs exemplify the strides the Swedish were making to establish their presence on the global stage and expand their economy beyond their stronghold in northern Europe in the 18th century.

Covered punch bowl and underdish depicting the Swedish Château of Läckö, on Lake Vänern. Made in China, ca. 1745-55. Porcelain (hard paste). In the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1940).

Covered punchbowl and underdish depicting the Chinese Pavillion at Drottingholm Palace in Stockholm, Sweden. Made in China, ca. 1763. Porcelain (hard paste). In the collection of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts (Museum purchase, 1999. AE85710.A-C).

Suecia antiqua et hodierna (Sweden ancient and modern) was a collection of published engravings based upon topographical drawings by Eric Dahlberg (1625–1705), an accomplished Swedish civil servant and draftsman. Through his over 400 drawings, Dahlberg hoped to make a visual argument for the glory of Sweden. Reproducing those designs onto porcelain also transferred those aspirations onto these luxury items, to be seen on the tables of the powerful Swedish families leading the charge to make Sweden a great European power.

Like these punchbowls, Winterthur’s oversized mugs are decorated with a topographical scene representing an extant Swedish landscape. However, they differ from those examples because rather than depicting an ancient estate from Suecia antiqua et hodierna, Winterthur’s mugs feature an industrialized landscape. The iron-red enamel scene in the central register of these large vessels features the buildings, terraces, and wooden bridge-covered stream of Furudals Bruk, one of Sweden’s foremost iron foundries in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Renowned for its production of iron chains, the foundry was originally founded in 1709.

The foundry’s third owner, Isaac Gustav Clason (1748–1804), purchased the foundry in 1776 and brought Furudals Bruk to the height of its success. Under his management it became one of the main suppliers of quality large ironwork in Sweden, even supplying the S.E.I.C. with chains and anchors for their ships! With the foundry thriving at the end of the 1700s, Clason decided to commemorate his success by commissioning a pair of stupendously sized Chinese export porcelain drinking vessels.

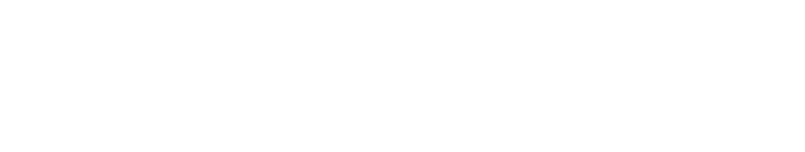

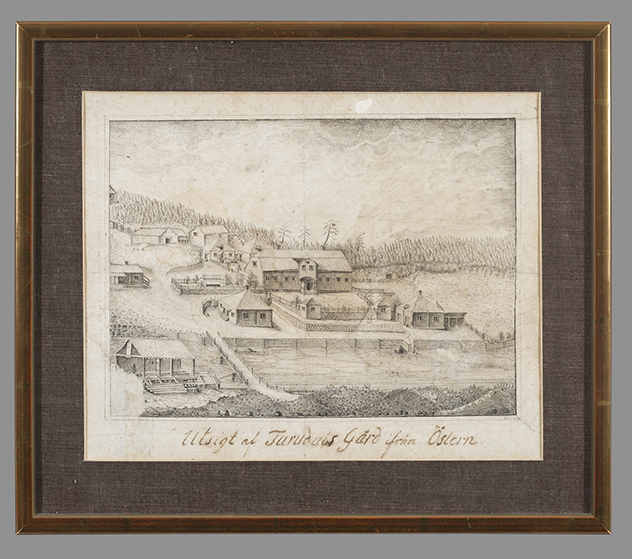

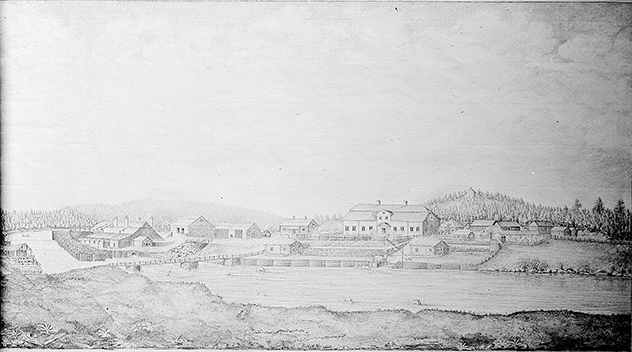

Rather than reproducing a grand estate, as might have been the choice of members of the Swedish aristocracy, businessman Clason chose to reproduce an image of his iron foundry. For the drawing, he turned to his friend Gustaf Henrik Hertzenhielm (1749–1804), a nobleman and major in the Swedish army stationed at Dalarna County (where Furudals Bruk was located). Hertzenhielm, reportedly a friend of Clason’s and perhaps an investor in his business, was also an amateur draughtsman and artist. In the 1790s, after a systematic examination of the foundry and the surrounding countryside, Hertzenhielm produced several graphite sketches of Furudals Bruk in the 1790s. A surviving sketch dated 1792 (also at Winterthur) was the direct inspiration for the mugs’ design.

Utsigt af Furudals Gård från Öslorn (Prospect of Furudals Courtyard from Öslorn). Gustaf Henrik Hertzenhielm. Sweden; ca. 1792. Graphite on paper. Gift of Julie and the late Carl M. Lindberg 2014.29.2.

Utsikt mot norra stranden med herrgården (View of the north beach with the manor house). Gustaf Henrik Hertzenhielm. Sweden, ca. 1775. Jernkontoret (Swedish steel producers’ association), library picture collection, Stockholm, Sweden.

Utsikt mot brukets strand (View of the beach of the resort). Gustaf Henrik Hertzenhielm. Sweden, ca. 1790. Jernkontoret (Swedish steel producers’ association) library picture collection, Stockholm, Sweden.

Clason likely sent his order for the mugs through his cousin, S.E.I.C. captain Hans Henrik Clason, who travelled to China on four expeditions between 1782 and 1794 (The Gullbringa service pictured in fig. 6 was owned by Hans). Following Clason’s death, the mugs descended in his family until at least the mid-20th century.

Although sadly empty of Swedish beer now, these exciting new additions to the Winterthur collection tell us a great deal about the global luxury goods market in the 18th century and the power plays being made by both individuals and nations alike in that period of rapid global change. Sweden, long mired in wars with its neighboring countries, sought to gain profit and power through the success of the S.E.I.C. Clason, a member of the self-made industrial class rising to prominence in the late 18th century, aspired to equal status with Sweden’s titled nobility. For both country and man, Swedish-designed, Chinese-produced porcelain was the key to achieving those goals.

Post by Nalleli Guillen, Sewell C. Biggs Curatorial Fellow, Museum Collections Department, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library

References

A special thank you to Ynge Axelsson and the library at Jernkontoret in Stockholm, Sweden, for providing invaluable references and information on Furudals Bruk and Gustaf Henrik Hertzenhielm.

Clason, Frederick. Furudals mill history. Stockholm: Published by grants from Prytz British fund. 1938.

Gotheborg.com, http://www.gotheborg.com/.

Hervouet, Francois et Nicole and Yves Bruneau. La Porcelaine Des Compagnies des Indes A Décor Occidental. Paris: Flammarion. 1986.

Motley, William (Cohen & Cohen). Double Dutch or, on with the Dance, Let Joy Be Unconfined: Asian Art in London Auction Catalog. 2-10 November 2006.

Örjens gille, Sancte. Med Hammare Och Fackla. Stockholm: Sancte Orjens gille. 1940-41.

Phillips, John Goldsmith. China-Trade Porcelain. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1956.

Pinto de Matos, Maria Antonia and Rose Kerr. Tankards and Mugs: Drinking from Chinese Export Porcelain. London: Jorge Welson Research & Publishing. 2016.

Roth, Stig. Chinese Porcelain Imported by the Swedish East India Company. Printed in Sweden: Elanders Boktryckeri Aktiebolag, Göteborg. 1965.

Sargent, William R. Treasures of Chinese Export Ceramics from the Peabody Essex Museum. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2012.

The Swedish Ship Gotheborg, http://www.soic.se/en/.